Global challenges, such as the housing crisis and climate change, have led to the unprecedented design of large-scale, master-planned, high-tech cities over the past two decades. New futuristic cities, built across many parts of the world, particularly in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, are attempts to create a relatively self-sufficient urban space geographically distinct from existing cities. Unlike extensions of existing urban centers, these purpose-built cities are autonomous entities that develop their own identities while offering a range of opportunities that make them attractive to the private sector.

For developing economies, futuristic cities present a chance to stimulate growth, gain global visibility, and even redefine national identities. Computer-generated visualizations used in their design depict utopian visions of smart “eco-cities” that promise a more modern and prosperous future.

In this article, we examine 10 futuristic cities planned for construction around the world in the coming years:

1. Telosa

Location: USA

Architect: BIG

Designed by Danish architect Bjarke Ingels for Marc Lore, Telosa, a city designed for a population of five million, is being designed with a new urban concept in the United States. Built from scratch on a 150,000-acre vacant lot in the Andes desert, this city will set a global standard for urban living in the United States, expanding human potential and becoming a model for future generations.

The first phase of the project, expected to be completed by 2030, will serve 50,000 residents, with the full development projected to host five million people by 2050. Positioned as a purpose-built city, Telosa offers a long-term vision that combines ecological resilience, technological systems, and an alternative governance model, creating a potential prototype for future urban development. Its urban design emphasizes accessibility and public space, placing schools, workplaces, and essential services according to the principles of the 15-minute city model. Mobility relies on bicycles, scooters, autonomous electric vehicles, and a Sky Tram network.

By combining renewable energy production, drought-resistant water systems, and environmentally friendly architecture, Telosa aims to create a framework for sustainable and equitable urban living. Located at the heart of the futuristic city, a wooden skyscraper called Equtism Tower is a landmark and a symbol of the city’s proposed economic model. Featuring aeroponic farms, photovoltaic roofs, and water-storage systems, the tower embodies the principle of Equitism, which ensures that land ownership and urban growth are structured to benefit all residents.

2. BiodiverCity

Location: Malaysia

Architect: BIG

Proposed by BIG in collaboration with Ramboll and Hijjas, the BiodiverCity master plan for the Penang South Islands is envisioned as a sustainable destination where cultural, ecological, and economic growth are secured, and where people live in harmony with nature in one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet. Encompassing 1,821 hectares, this master plan aims to connect three artificial islands with an autonomous transportation network. Each island, modeled after a lotus leaf, will comprise mixed-use neighborhoods, 4.6 kilometers of public beaches, 242 hectares of parks, and a 25-kilometer coastline.

Each island district is planned to accommodate between 15,000 and 18,000 residents, while much of BiodiverCity’s construction will use a combination of bamboo, Malaysian timber, and “green concrete” made with recycled materials. Relying on local water resources, renewable energy, and waste management, BiodiverCity will be connected by an autonomous water, air, and land transportation network, creating a car-free environment. A network of ecological corridors, called buffers, ranging from 50 to 100 meters, will be located around the buildings and neighborhoods, serving as nature reserves and parks to support biodiversity.

In the master plan, the first island, called The Channels, will include Civic Heart, an area hosting government and research institutions, as well as the Culture Coast, a district inspired by the state capital, George Town. A 200-hectare digital park located at the heart of the island will invite locals and visitors to explore the world of technology, robotics, and virtual reality. BiodiveCity’s second island, Mongrovers, will house Bamboo Beacon, a facility for conferences and large events. The final island, Laguna, described by BIG as a miniature archipelago, comprises eight smaller islands arranged around a central marina.

3. Toyota Woven City

Location: Japan

Architect: BIG

Designed by BIG for Toyota as the “mobility of the future,” the smart city Woven City is located on the former 70-hectare site of Toyota Motor East Japan’s Higashi-Fuji Plant in Susono City, Shizuoka Prefecture, near the foothills of Mount Fuji. Designed as a living laboratory to test and develop mobility, autonomy, connectivity, hydrogen-powered infrastructure, and industrial collaboration, this futuristic city is a 175-acre cluster. The project aims to create a close-knit human community within a defined environment and proposes a connected city that establishes a new balance between vehicles, alternative mobility modes, people, and nature, envisioning a carbon-neutral society.

Toyota Woven City is shaped around three core concepts: a living laboratory, a people-centric and continuously evolving city, and a woven city. This intersection of social infrastructure, mobility, and people offers innovators, residents, and visitors a unique opportunity to seamlessly interact with new technologies throughout daily life in an environment that mimics a real city.

Powered by solar energy, geothermal energy, and hydrogen fuel-cell technology, the city establishes a flexible street network dedicated to various mobility speeds to ensure safer, pedestrian-friendly connections. The traditional road system is disrupted, dividing public space into three entities: a main street for faster autonomous vehicles, a recreational promenade for micromobility types, and finally, a linear park dedicated to people and nature.

Designed with a 150-meter-wide woven grid plan, the 3×3 city blocks of Woven City each encircle a courtyard accessible solely through the promenade or linear park. Expected to house 2,000 people, the city’s mostly timber-built houses feature rooftop solar panels, while apartments are designed to provide residents with access to impressive terraces.

4. New Administrative Capital

Location: Egypt

Architect: SOM

Constructed on a 700 km² site approximately 45 kilometers east of Cairo, Egypt’s New Capital was designed by SOM to suit the region’s cultural and climatic conditions. Designed to address the country’s growing population density, traffic congestion, and environmental challenges, this futuristic city’s master plan will support a growing economy while also creating a sustainable city.

Designed to accommodate a population of seven million, the New Administrative Capital will ease Cairo’s rising population pressure by organizing the new urban district into commercial, administrative, cultural, and innovation zones. The city offers 100 unique residential housing opportunities, ranging from medium to high density, shaped by climate conditions. Passive cooling will be provided by natural ventilation, and local plant species will be used in the landscaping.

The new city, characterized by its compact urban form, replicates some of Cairo’s existing development patterns. Surrounded by a central public space housing shops, schools, religious buildings, and other functions, each neighborhood not only enhances accessibility but also reflects the neighborhood’s identity, drawing inspiration from the area’s traditional settlement patterns. Complementing Egypt’s national vision for a new renaissance, the New Administrative Capital represents a rare opportunity for citizens to express their aspirations for a better quality of life for all.

5. Amaravati

Location: India

Architect: Foster + Partners

Designed by Foster + Partners, the city of Amaravati is planned as the new capital of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. This futuristic city, located on the banks of the Krishna River and spanning 217 kilometers, is strategically positioned to benefit from abundant freshwater resources and is poised to become one of the world’s most sustainable cities.

The Amaravati master plan includes the design of two major buildings: the Legislative Assembly and the High Court complex, along with several secretariat buildings that will house the state administrative offices. The government complex, measuring 5.5 x 1 kilometers, is located at the heart of the city and is defined by a strong urban grid that structures the city. A clearly defined green spine, with at least 60% of the area covered by greenery or water, forms the foundation of the master plan’s environmental strategy.

Designed to the highest sustainability standards using the latest technologies currently being developed in India, the city’s transportation strategy includes electric vehicles, water taxis, and dedicated bicycle paths, as well as shaded streets and squares to encourage people to walk around the city.

South of the riverfront lies a mixed-use neighborhood centered around 13 urban plazas, symbolizing the 13 districts of Andhra Pradesh. A democratic and cultural landmark, the Legislative Assembly building is located at the center of the green spine and is surrounded by the secretariat and cultural institutions. Based on Vaastu principles, the square-plan building has a public entrance from the north, while the ministerial entrance is from the east. Designed as a courtyard-like space, this center serves as a meeting space for the public and elected representatives. Protected by a 250-meter-high conical roof and a projecting eave, the building’s spiral ramp leads to the cultural museum and viewing gallery.

Situated off the central axis, the High Court complex features a stepped roof inspired by India’s ancient stupas. The roof’s deep overhangs not only provide shade but also naturally ventilate the building. Inspired by traditional temple layouts, the plan consists of alternating concentric rooms and circulation zones. The most public areas, the administrative offices and lower courts, are located on the outer edges of the building, while the interior spaces are reserved for the Chief Justice’s court and private chambers.

6. Smart Forest City

Location: Mexico

Architect: Stefano Boeri Architetti

Focusing on innovation and environmental quality, Mexico’s first Smart Forest City was commissioned by Grupo Karim, and its master plan was designed by Stefano Boeri Architects. This futuristic city, an urban ecosystem where nature and the city intertwine as a single organism, is designed to pioneer ecologically efficient developments. Located on a 557-hectare site near Cancun, Smart Forest City offers accommodation for up to 130,000 people.

Based on an open and international urban design concept inspired by technological innovation and environmental quality, the Smart Forest City will feature 362 hectares of cultivated land and 120,000 plants from 350 different species selected by landscape architect Laura Gatti. A high-tech innovation center, part of Forest City, is a space where university departments, institutions, laboratories, and companies can address important global challenges such as environmental sustainability and the future of the planet.

Smart Forest City is designed as a self-sufficient settlement for energy production, supported by a ring of photovoltaic panels and a water system connected to the sea through an underground channel. This setup encourages the development of a circular economy centered on water use. Water is collected at the city’s entrance by a large pier and a desalination tower, and distributed through a system of navigation channels to residential areas and surrounding agricultural lands. Designed as a pioneer in mobility, Smart Forest City is all-electric or semi-automatic, requiring residents and visitors to abandon all internal combustion engine vehicles within the city limits.

Designed according to the principles of Uncertain Urban Planning, the city allows remarkable flexibility in the distribution of architectural and building types. A botanical garden within a contemporary city, Cancun’s Smart Forest City is rooted in traditional local heritage and a connection to both the natural and sacred worlds. The path to detoxified and immaterial goods and services is comprised of the four Rs: reduction, repair, reuse, and recycling. By pursuing radically more eco-efficient solutions, beginning with reducing overall energy demand and waste generation, the Smart Forest City addresses these development needs by improving lifestyles and behaviors, particularly through the education and economic empowerment of women.

7. The Orbit

Location: Canada

Architect: Partisans

Designed by Partisans in anticipation of the arrival of high-speed mass transit connecting it to downtown Toronto, The Orbit is a vision for a state-of-the-art central neighborhood in the town of Innisfil, Canada. By combining autonomous vehicles and drone ports, the project aims to transform a Canadian town into a smart community, while preserving the existing agricultural and lush green environment, and incorporating a range of new technologies into a city of the future. The city, which integrates a fiber optic network—wires that quickly transmit information using optical technology—will connect development areas such as sidewalks, streets, and buildings.

Representing the next stage of growth for Innisfil, The Orbit spans 450 acres and extends the garden-city tradition by embracing the town’s agricultural roots alongside 21st-century urbanism and architectural thinking. The Orbit boasts over 40 million square meters of built-up area. Home to 150,000 residents, the project will create a dynamic hub of activity for visitors and residents.

Eliminating the need to leave the area, the master plan will include a full range of community amenities and spaces within walking distance, including a school with a daycare center, office space designed for local entrepreneurs and traditional and non-traditional industries, year-round sports and recreation options, arts and cultural spaces, and more. The project’s health and wellness campus will be connected to larger hospitals in the area through technology.

8. Maldives Floating City

Location: Maldives

Architect: Waterstudio.nl3

Designed as a benchmark for vibrant communities, the Maldives Floating City is the first “island city” located in a 200-hectare warm-water lagoon just 10 minutes by boat from Male. This project, the world’s first true floating island city, is inspired by traditional Maldivian maritime culture. Consisting of thousands of residences floating on a functional grid, the Maldives Floating City will accommodate 20,000 people.

Embracing sustainability and livability in equal measure, the Floating City is rooted in the local culture of a seafaring nation that celebrates the strong bond between Maldivians and the ocean. The project stands out with its boat-based community, where canals function as logistics and transit routes, and land-based transportation is limited to walking and cycling on natural white-sand pathways. MFC features a nature-based network of roads and waterways efficiently organized like real brain coral formations. Designed with the concept of “next-generation sea-level rise-resilient urban development,” combining green technology, security, and commercial viability, the city transforms the Maldives into a climate innovator.

Responding to dynamic demand, weather, and climate change, the smart grid utilizes innovative sustainable development technologies and proposes ecological practices to protect, preserve, and enhance the marine ecosystem. Constructed at a local shipyard, the units are mounted on a large underwater concrete hull anchored to the seabed on telescopic steel legs. The underwater coral reefs, along with a network of interconnected floating structures, will act as natural wave breakers, providing comfort and safety for residents.

9. Chengdu Future City

Location: China

Architect: OMA

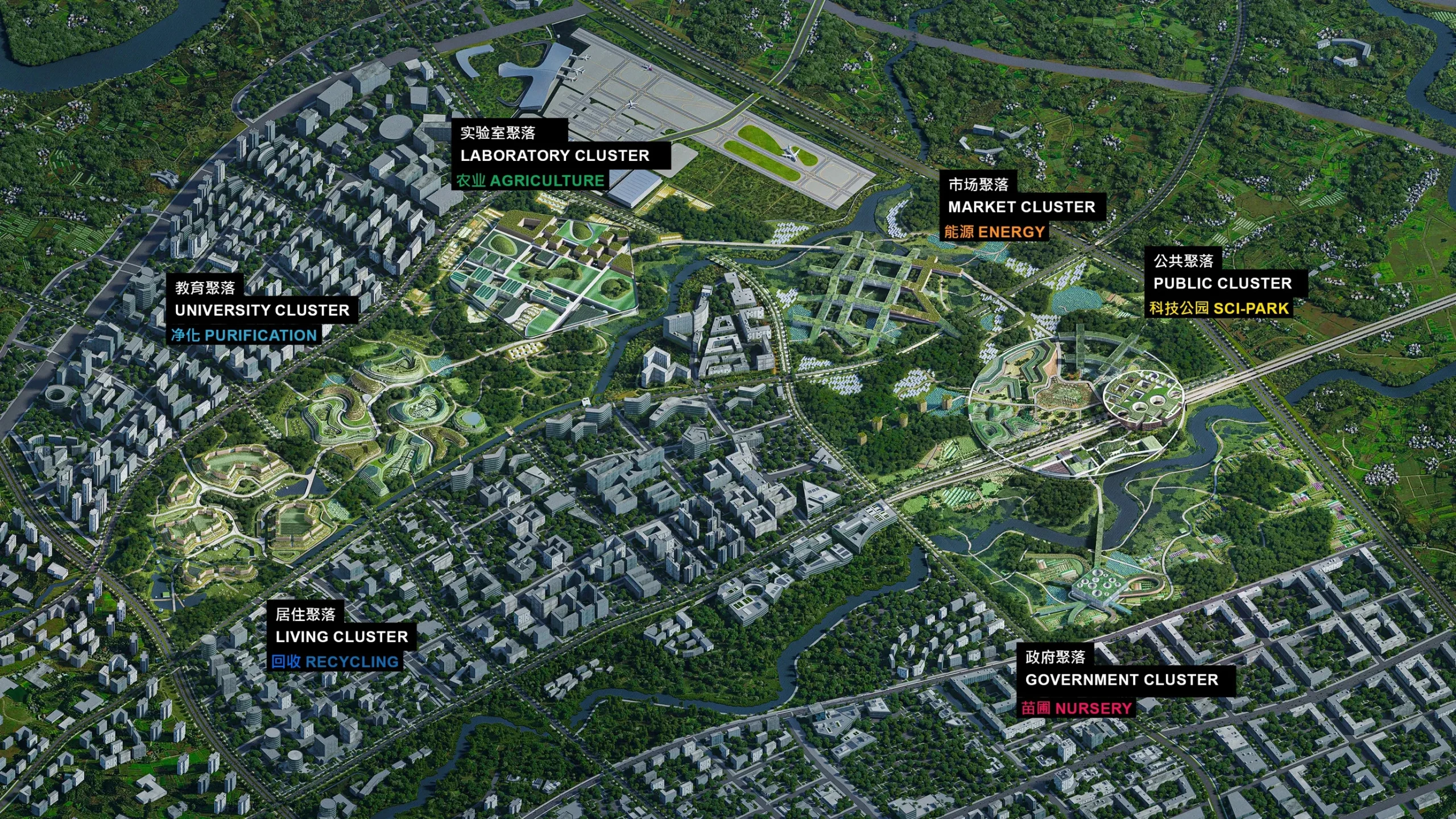

Designed by OMA for the capital of China’s Sichuan province, Chengdu Future City is a car-free master plan that focuses on the region’s existing geography and topography. The city, shaped by the question, “How can a master plan for the innovation industry be innovative in itself?”, defines the urban typologies and their organization within the existing topography, greenery, and water systems program on the site, resulting in a new type of master plan that combines urban and rural qualities in China.

Inspired by the Lin Pan villages of Chengdu, the 4.6-square-kilometer master plan consists of six clusters, each defined by its program and highlighting a specific architectural typology and its relationship to topography and local water systems. The Living Cluster, featuring commercial programs on the ground level and residential developments above, is centered around a reservoir that evokes the site’s water elements.

The University Cluster, featuring hill-like landscaped terraces, will feature a biofiltration system where the buildings’ extensive rooftops will become rain gardens, filtering water and collecting it in underground storage tanks and ponds. The University Cluster is connected to the Laboratory Cluster, located in the wetland, by walkways and bicycle paths. Featuring research gardens, the Laboratory Cluster also includes rooftop agricultural systems equipped with facilities for innovative experiments.

The Market Cluster, an elevated grid structure with commercial and public facilities on the ground floor and residential developments and offices above, is characterized by its use of hydroelectricity. The Public Cluster, a raised circular volume to which all train and transportation facilities will be connected, will be a Transportation-Oriented Development (TOD) with public spaces and support for research, exhibition, and production programs. Situated atop a riverfront hill, the Government Cluster comprises five office buildings encircling a central block.

All clusters will be free of vehicular traffic and scaled so that every destination is reachable within ten minutes. They will be connected to the train station and surrounding urban areas through an intelligent mobility network designed for autonomous vehicles.

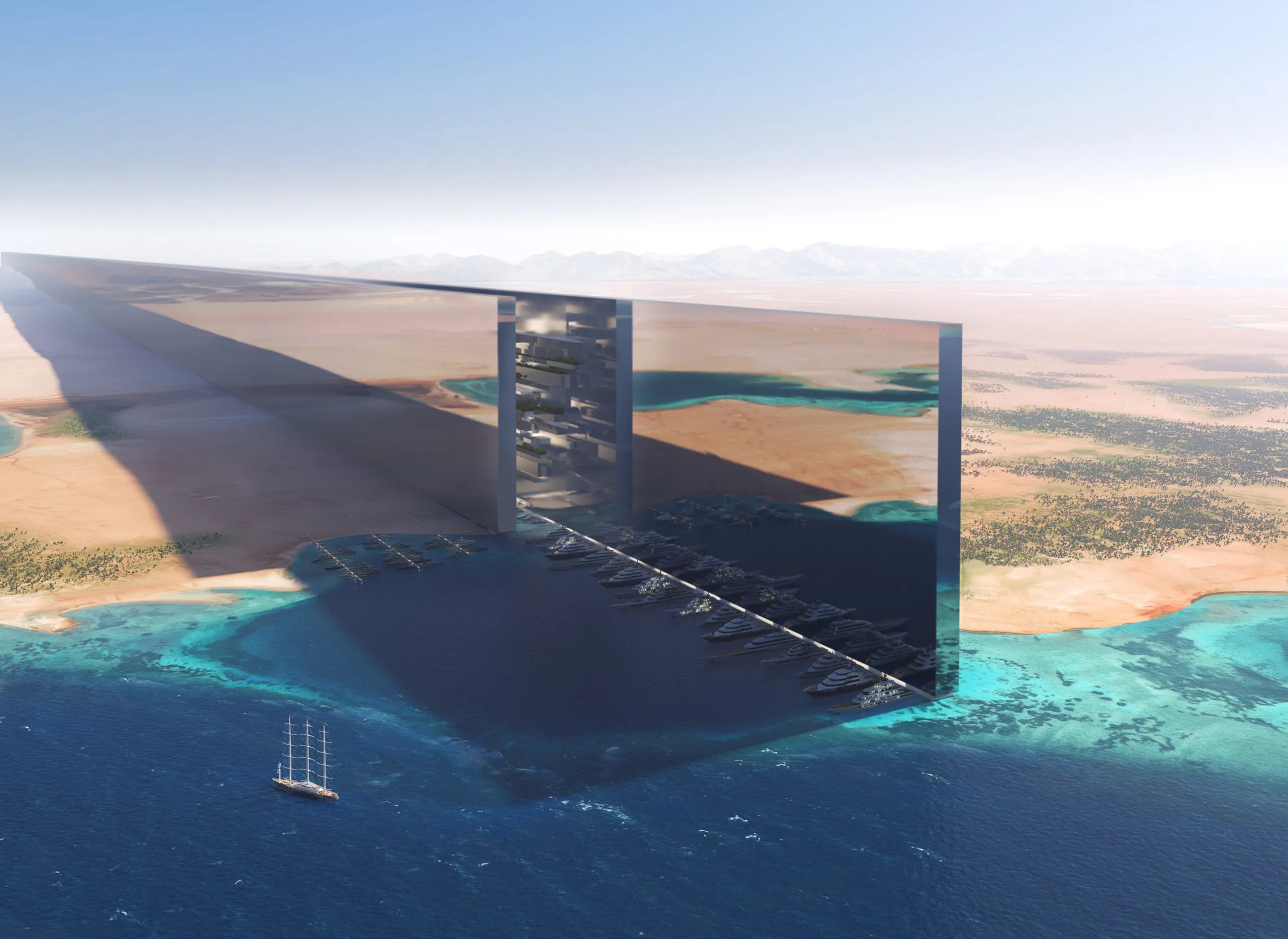

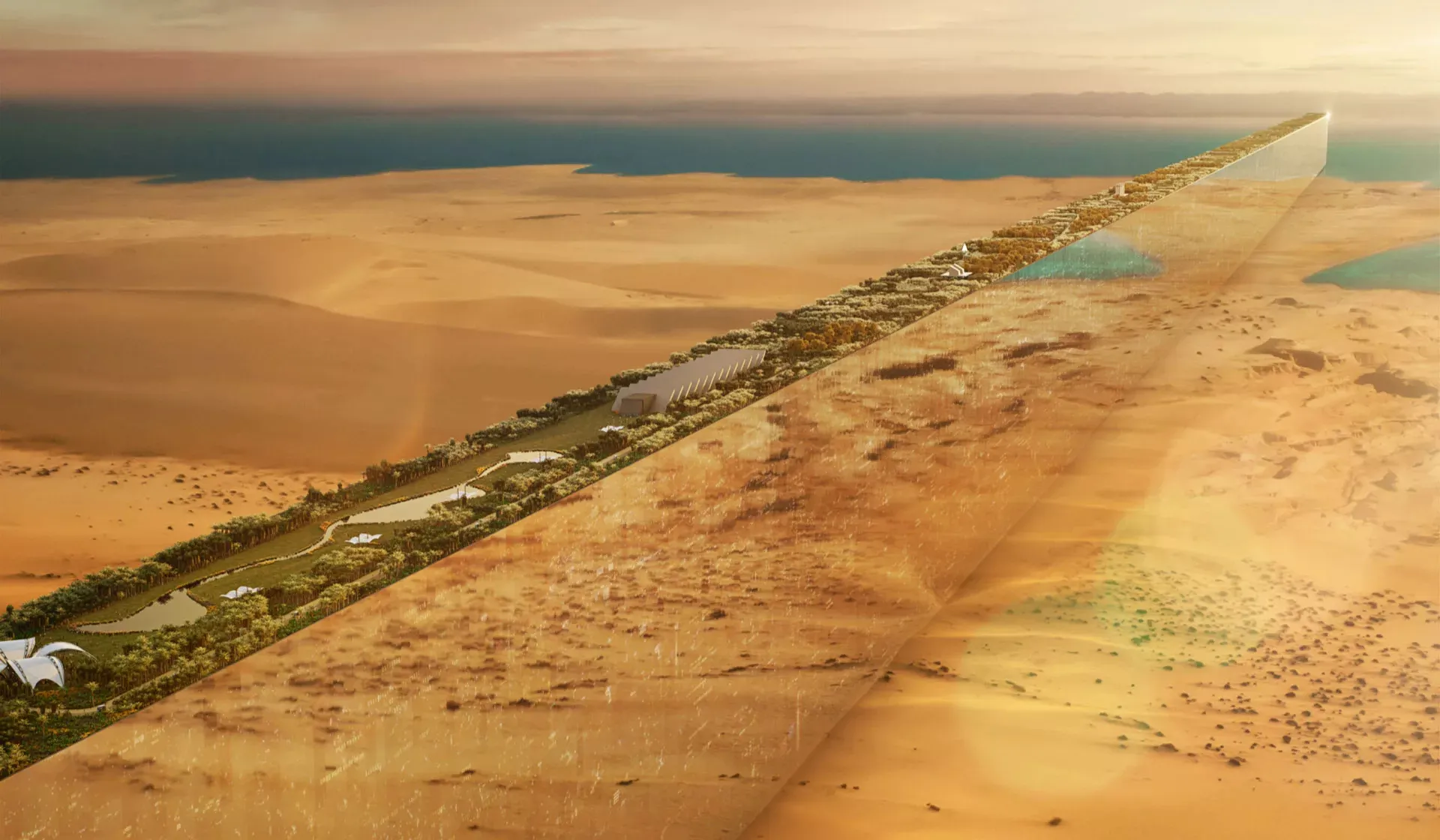

10. The Line

Location: Saudi Arabia

As one of the most ambitious architectural and urban projects of the 21st century, The Line, designed within the NEOM (New Future) development, serves as a model for preserving nature and enhancing human life. Planned to be built along a 170-kilometer stretch in northwest Saudi Arabia, the megastructure with mirrored facades will be 500 meters high and 200 meters wide.

A dramatic alternative to traditional cities that radiate from a central point, The Line addresses the challenges humanity faces in today’s urban life and illuminates alternative lifestyles. Comprised of two wall-like structures with open space between them, the city will be the 12th-tallest building in the world upon completion and by far the longest structure. The project, expected to house 9 million people, will include housing, shopping, and recreational areas, schools, and parks. Designed with the principles of Zero Gravity Urbanism, The Line will layer various functions.

Featuring a mirrored exterior façade that defines its unique character and enables even its minimal footprint to blend into the natural surroundings, The Line’s interior is designed to offer extraordinary experiences and immersive moments. A transportation system will run the length of the megastructure, connecting the two ends of the city in 20 minutes.

![iStock-1159286772-machine-learning-AI [Trimble] Vector Polygon dot connect line shaped AI. Concept for machine learning and artificial intelligence.](https://i0.wp.com/www.pbctoday.co.uk/news/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Trimble-and-AI-696x445.jpg?resize=696%2C445&ssl=1)

You must be logged in to post a comment.